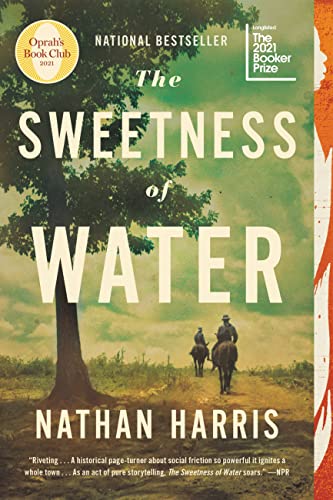

By Nathan Harris

June 15, 2021 • 368 pages

4.5 / 5 Stars

Recently freed brothers Prentiss and Landry make a temporary home in the forest of Old Ox, Georgia, where they bide their time, penniless but innovative despite their circumstance, before they head up north to search for their mother who had been sold before the war.

George Walker, a northern man replanted in Old Ox, Georgia, comes across the two men on this daily jaunts through the forest, where they forge a tentative agreement— assist George in reviving his farmland in exchange for equal pay that the brothers can use toward their journey north.

The point of view in the novel shifts from multiple perspectives including Landry, Prentiss’s silent, slack-jawed brother; George’s wife Isabelle, a practical yet deeply sentimental woman; and their son, Caleb—a fragile soldier tangled in an illicit affair with his (toxic!!!) childhood friend, August.

While Half of Old Ox struggles with the passing of the Emancipation Proclamation and the other half forges onward with their newfound freedom, conflicting ideals and underlying resentments begin to seep out from the underbelly of the confederate south, culminating in a murder, an escape, and a roaring fire that alters the land and its people in irrevocable ways.

The first thing that stands out to me in the Sweetness of Water is the writing. Harris writes in sweeping motions, tender gestures, and a lyrical thoughtfulness that make an ordinary moment feel profound—like it’s a painting that should be hung carefully and beheld—

“He told me once about a field,” Prentiss said, stopping her. “It took him just about a whole morning to get the words out his mouth, but he told me. Said he went out in the woods and found a field of dandelions, so many together that the ground was white as snow, and he sat there for a time thinking, and in the time it takes your heart to beat, a gust of wind poured through that field and every single seed shot up into the air, ain’t a single one left on the ground, and the whole sky was bright with their travels, and then they were gone?” Isabelle stood there frozen, contemplating the image.

— and he can make a tragedy many chapters back, feel more haunting and visceral.

“What you think I be looking out at all day? In the woods. I see my brother every which way I turn, beaten and bruised, blood running down his face. I been seeing my mama ever since she been sold […] Half the time you wake me up I think it’s Gail rousing me for lazying up a proper workday. I s’pose that boy August gon’ be outside your window for the rest of your days. That’s how them demons work. How them ghosts follow you around. Be proud you gone out and faced him straight on. Ain’t everyone brave enough for that. But you should know it ain’t gonna change nothing. You still gotta get up each morning. Still gotta settle down each night. So if you ain’t gonna get some rest for yourself, at least let me get mine.”

He knows when to be serious and when to be witty, and when to interweave these contrasting tones into one seamless exchange.

“You know,” George said, “when I look in the mirror in the morning I see a miserable old bastard looking back at me. Yet when I see you, I take great comfort, knowing how much progress I have left to make on that same path?”

And

“George, I ain’t got the slightest clue what you’re talking about. But I got half a mind to shove this hoe right up your ass.”

“Always voicing one threat or another.”

“I’d be right glad to turn it into a reality for you. I’ll lay you out on my knee and stick the handle of this hoe so far up your behind you’ll be able to turn your soil with a squat and a shuffle.”

The main characters are crafted with thought and intention, with their own deeply moving internal musings, conflicts, demons, and purposes, but some seem unrealized. August, for instance, feels like a shadow of a man for most of the novel but is, ironically, the character that incites the climax of the story, allowing for the rest of the conflicts to unfold. Toward the end of the novel, other characters begin to break from their molds in almost unrealistic ways. Webler, August’s father, calls off his revenge for the Walkers after one of their arguments comes to a head; and George, for all his strength and tenacity in the beginning, turns fragile and flimsy toward the end. Caleb, once cowardly and unsure for most of his life, suddenly finds a bravery I couldn’t logically see him coming to out of nowhere; and August just disappears.

For me, Isabelle is the unforeseen star who steals the show. She reminds me of lava, slowly moving beneath the surface and altering the landscape in silent but profound ways. Sounds like I’m trying hard to make a metaphor of her character, but that’s the only way I can think to explain her. Throughout the novel, she is steady and consistent. Witty and strong-headed. Brave and compassionate without pretension.

[One other internal debate I had with the novel was an almost pervasive feeling of white saviorism, but that’s something I’d rather unpack in a conversation rather than a review.]

The Sweetness of Water may be about the consequences of a segregated society, of life-long journey of grief, and of the tenacity of hope, but to me its most pervasive theme is love—in all its forms: romantic, platonic, and familial. It is a catalyst for the novel’s main conflict, and the single force that fuels their hope and bravery, and it is the pillar the characters rest on before making the choices that change the lives around them.

“There was a rhythm to their eating. One would take a bite, and then the other, and it was in these slight recognitions—no different from the way they exchanged deep breaths while falling asleep— that the brushstrokes of their marriage coalesced day after day, night after night, the resulting portrait rewarding but infuriatingly difficult to interpret.”

I felt as if I was a stranger peering into the lives of these people, watching the tiny details of their complex relationships unfold, always removed but invested.

“It was a mutual passion for independence that had brought [George and Isabelle] together in the first place, the ability to go through vast segments of the day in silence, with only a glance, a touch on the back, to affirm their feelings. In doing so the bond between them had strengthened over time, and although it was not prone to bending, its single weak point lay in the quiet embarrassment that it existed in the first place that two individuals who resolutely dismissed the idea of needing anyone else were now helpless without each other.”

Despite my few issues with the novel, as a whole it is a stunning work of Literature (yes, capital ‘L’ Literature!), and I look forward to more works by Harris.

Leave a comment